The best way to really learn data analytics is to apply what you’ve learned in classes and videos to process and analyze real, messy, complicated data. You may be lucky and have the resources and time to do this all at work. If not, you’ll likely be doing side projects in your spare time to build skills. You’ll have to start with finding a data set.

A good dataset is one that pertains to a topic that interests you, has enough observations (rows) to allow you to find patterns, and enough variables (columns) to give you practice deciding what’s important or what’s not.

I recommend starting with a question you have about the world, and then looking for data to help you answer that question. This will motivate you to keep going when it’s tough, and give you an end result you’re proud to share with the world. So where do you start? Here are some transportation-related data sources to consider.

Metropolitan Planning Organizations

Metropolitan planning organizations (MPOs) are regional planning bodies that administer federal grants for their region. Every metro area in the United States is required to have one, and they often publish great data. A data source that I’m fond of locally is our Puget Sound Regional Council’s Household Travel Survey, a survey of the travel habits of households in the region. They ask participants to log every trip they take for a week and also ask attitudinal questions such as how one feels about autonomous vehicles. In survey data, you are almost guaranteed to find missing data, but dealing with it is a skill you will always need, so better get to practicing. Find your local MPO here and see what data they can offer you.

Open Data Portals

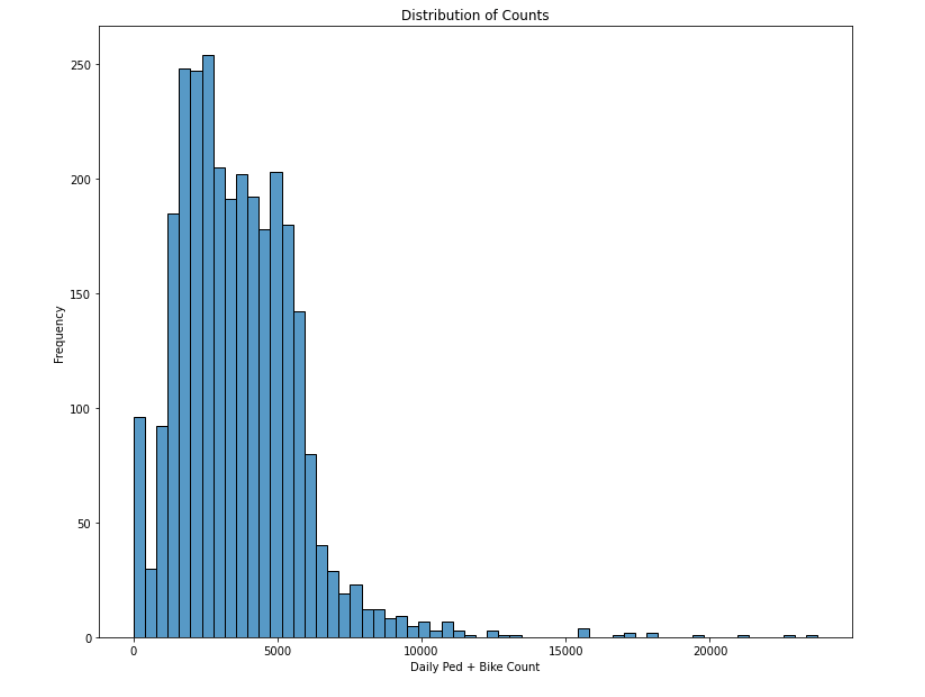

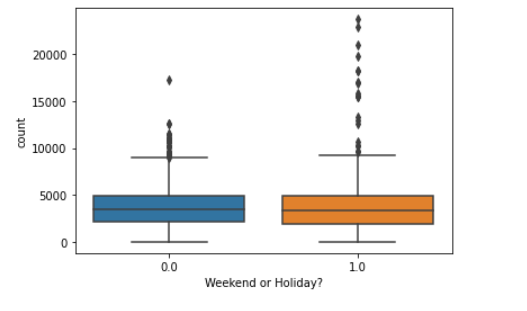

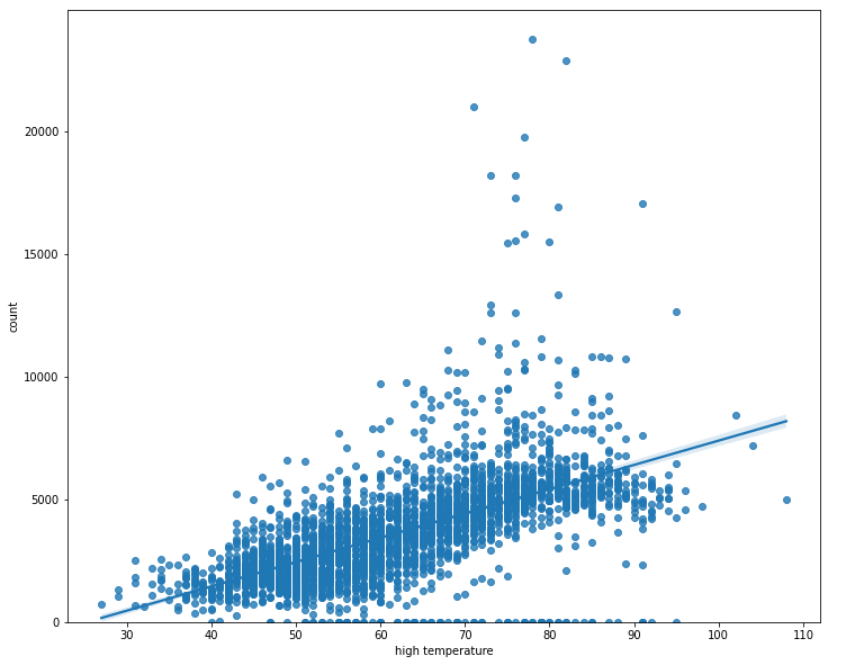

I’ve written before about Open Data Portals that nearly every government seems to provide these days. From the transportation side, these can provide data on traffic or freight volumes, pedestrian and bike counts, or transit usage. They have the benefit of being fairly complete because they are collected passively, though I’ve seen device malfunctions create missing data in some instances. In addition to transportation, you can often find data about housing, criminal justice, and education. A lot of these will be time-series data, and working with that is also a good skill to develop.

Flight Radar24

For a different mode of transportation, think about all the data produced by the thousands of flights taken around the world each day. A fellow student in my statistics program recommended FlightRadar24 as a source of data on airplanes, flights, and airports, including real-time locations as shown above.

The ACS, a yearly survey by the US Census Bureau, asks several commute-related questions, such as what time respondents leave for work and what mode of transportation they use to get there. This data has already been processed and cleaned, missing data is minimal, and you’ll get practice learning how to deal with census tracts or other geographic units. Unfortunately, all this processing takes time and by the time you see it it’s usually 1-2 years old or more (as of writing, the most recent ACS data available is from 2019). Also, due to tightening privacy restrictions, data is less detailed than it once was and there are fewer data sets available at the individual respondent level.

Kaggle

Kaggle is perhaps the best-known website for crowd-sourced datasets and also a robust data science community. Spanning a variety of topics, these datasets are available to anyone with a free account and are easily searchable. I will say that some of these – The Titanic, home prices, and any covid-related dataset – have been used quite a bit, so consider something a bit more novel if you are hoping to publish your results somewhere like medium.com. These data sets may also have fewer guarantees of quality or accuracy, because anyone can contribute. Nonetheless, there is a lot here to explore. Kaggle also hosts data competitions for entry-mid level data scientists and folks still learning.

I hope this inspires you to get out there and find a data set you’ll enjoy playing with. What data sources do you use when exploring and learning?