And why data professionals need to be creative.

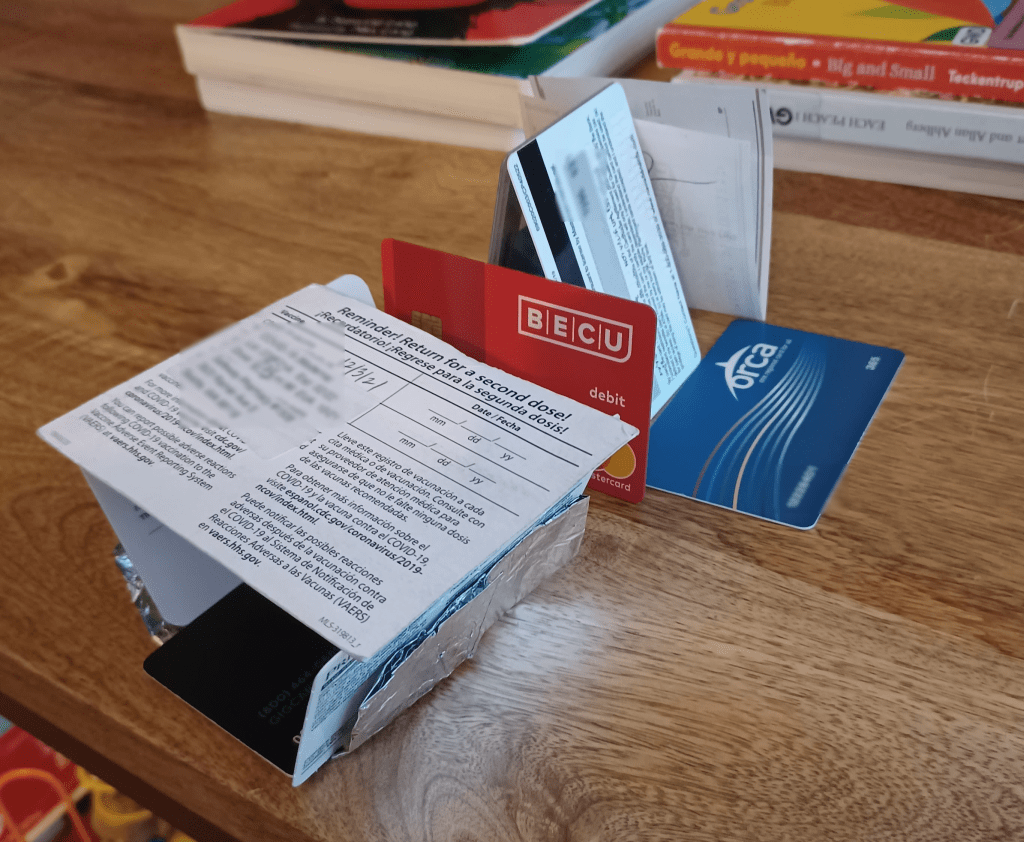

On a quiet night a few weeks ago, I found myself staring intently at a pot of water as it boiled, removing all the contents from my wallet, and then using them to build a rendering of my dream house.

Not what you did with your Tuesday night? Let me back up a bit and explain.

For as long as I can remember, I’ve understood that going running provided a sacred time when I could hear myself think. I let my mind wander, free of music or podcasts. I’ve thought through many big life decisions and transitions on runs.

These days, though, a few-times-a-week-run isn’t enough. I need more time than ever to slow down, process my life and the world around me, and just breathe.

So I was intrigued when I heard about the Bored and Brilliant project, a podcast-turned-book by the same name that explained “how spacing out can unlock your most productive and creative self.”

The idea is that getting away from distractions (particularly your phone) will give your brain space to be creative, problem solve, and plan your life, in ways you just don’t have space for when you are constantly being stimulated. The book culminates in a week-long finale of six daily challenges with the aim of getting you nice and bored.

I figured this could help me both personally and professionally and I was down for a challenge, but knew it would be more fun in community. I sent an email blast to a bunch of friends, and got a dozen or so to be curious enough to join me. I decided that I would send them one challenge a week for six weeks and would host three dinner parties over the course of the stint so we could share our experiences in real time.

Some challenges were not that hard: it turns out I’m not addicted to any apps. Some were fun: I learned some new Mexican slang by eavesdropping on a train full of soccer fans. Others had results I’d hoped for: not touching my phone while on the train really did lead to flashes of insight about problems at work. I could try this approach to my Power BI quandary! I forgot to control for this variable in my analysis!

But that challenge also surprised me. I found that I not only had more time to think about my own life, but I had more time to think about others. I would suddenly remember: My friend had a job interview. My mom had a doctors appointment. I should call and see how it went. I felt at once more introspective and more engaged with the world.

So back to that quiet night watching water boil and fishing credit cards out of my wallet. This was the culmination of the six-part challenge and it succeeded in getting me exorbitantly bored in order to set me up for a creative task: building my dream house. To be honest, I’m not that impressed with the dream house I concocted with mostly plastic cards found in my wallet. But I did get a lot of thinking done while watching for signs of the slightest bubble rising from the bottom of the pan.

That was enough to convince me that boredom is going to be a regular part of my life from now on. When I find myself with too much stuff in my head, the solution may not be yet another productivity app, but time to just space out and let my brain do what it knows how to do in the background.

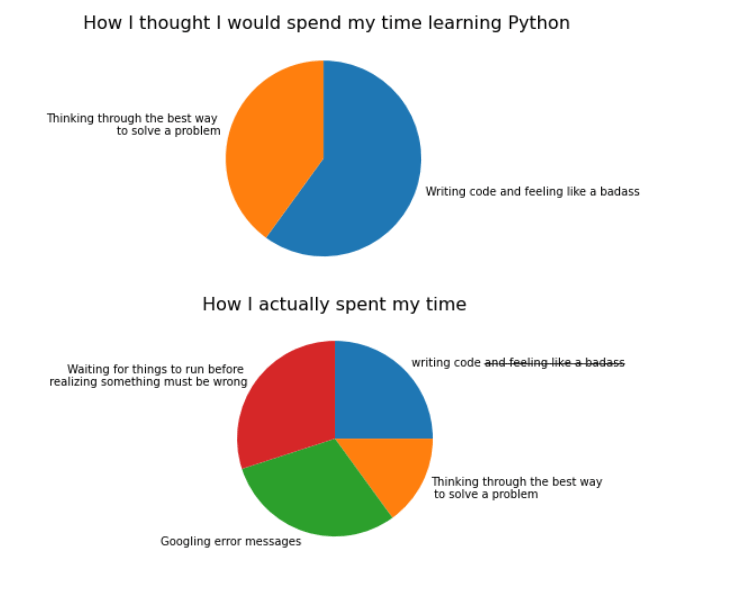

Why am I writing about this here? Because creativity and problem solving are skills we all need, and not the least in data professions. These skills make our work more fulfilling, and they set us apart from the Robots Coming For Our Jobs. Machines can crunch numbers, but humans decide which numbers need to be crunched to answer the question at hand and, more broadly, if that question is even the right one to be asking. If you’re feeling stumped, a little boredom may also be just what you need to get that spark of insight on how to approach the problem differently.

I challenge others to engage with this project either by reading Bored and Brilliant: How Spacing Out Can Unlock Your Most Productive and Creative Self by Manoush Zomorodi, or cut straight to the challenges with the more pithy WNYC podcast, hosted by the same author.

Let me know how it goes!