I recently participated in my first datathon along with two coworkers. A datathon is a competition where teams of participants gather and analyze data in order to solve (or at least chip away at) a real-world problem. It was a worthwhile experience that I recommend to others wanting to hone your data chops!

My datathon was through Women in Data and focused on women’s equality in the workplace. My team asked the question: What role does salary negotiation play in the gender pay gap?

Because we couldn’t find any dataset on salaries and negotiation, we created our own with a survey. Respondents reported about a recent job offer they received: the amount the employer offered, the amount they the candidate counter-offered, and the amount of the final offer from the employer.

We pushed the survey out through our networks and various Reddit pages, lacking the funds or time to get a random sample. This type of data collection is known as a convenience sample and is not statistically rigorous, so it’s important to note that the results we collected are true for our sample only and cannot be generalized to the whole population. Our 175 respondents were 49% white women, 24% women of color, 24% men, and 4% non-binary. In order to preserve reasonable sample sizes for each group, we don’t disaggregate any further in our analysis.

With that caveat out of the way, here are some highlights from our research:

Women Didn’t Negotiate as Often or as Hard

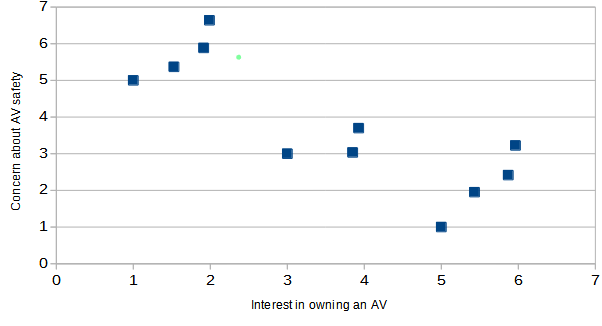

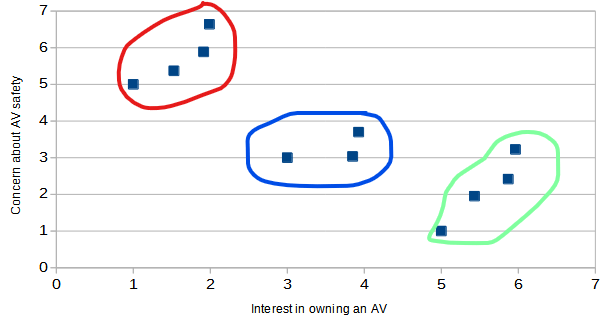

The women in our sample did not attempt to negotiate as often as men did, and did not negotiate as aggressively when they did. This graph shows the amount that each candidate attempted to negotiate as a percentage over the employer’s original offer. The tallest column shows that over 40% of white women and women of color did not counter-offer at all (at least not for salary – we did not ask about non-salary benefits).

As the chart suggests, men on average asked for the highest increase when counter-offering:

| Group of Respondents | Average counter-offer over the employer’s original offer |

| Women of color | 10.5% |

| White women | 6.5% |

| Men | 14% |

| Non-binary* | 5% |

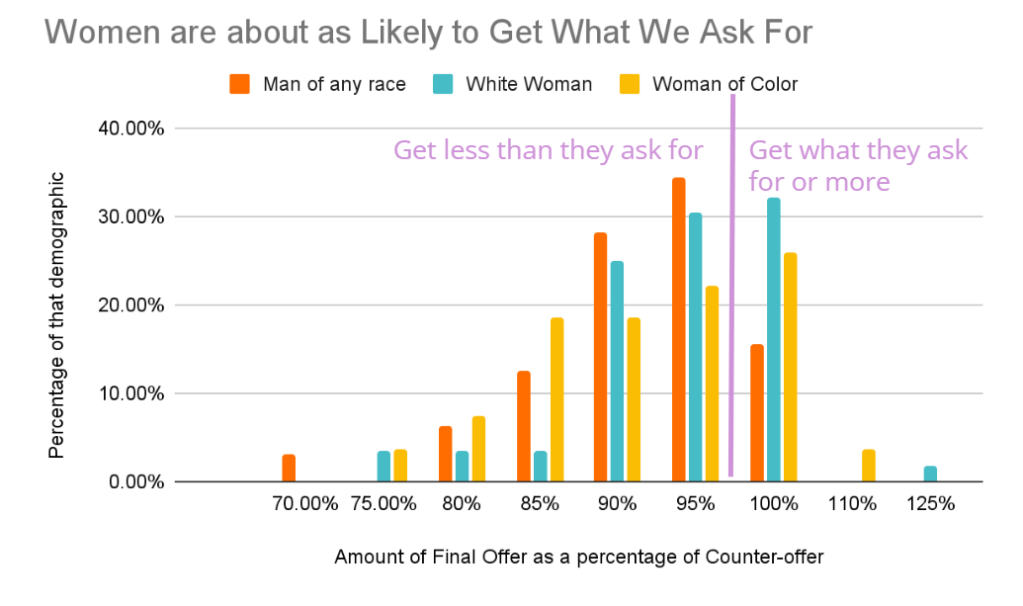

But when women did negotiate, they were about as likely as men to get what they asked for.

Though women didn’t negotiate as much, when they did, employers were about just as likely to give them what they asked for as they were for men. This graph shows how likely men, white women, and women of color were to get what they asked for when negotiating.

Averages of this data are shown below. 100% would mean the candidates got everything they asked for.

| Group of Respondents | Average final offer as percentage of counter-offer |

| Women of Color | 95% |

| White Women | 98% |

| Men | 95% |

| Non-binary* | 95% |

| Overall | 96% |

Of course, keep in mind that women are asking for less, so it’s easier to get what they ask for. Would they get more if they asked for more? There’s only one way to know!

Posted salary ranges discouraged negotiating… but only among women

Women who did negotiate were more influenced than men by whether the job posting included a salary range. When one was posted, women who did negotiate, asked for less money compared to when a range was not posted. The presence of a salary range has little effect on men, however. Perhaps if women were offered close to the top of the range, they felt that there was no sense in negotiating.

So What?

We hope our datathon work adds a little to the conversation on pay equity. Some takeaways for candidates are:

- Negotiate, even if a salary range is posted.

- Know that it’s normal to not get all that you ask for, and that’s ok.

And for employers: it would be great to collect data on what you are giving candidates compared to what they ask for, and whether this varies by gender and race.

Opportunities for more research

To keep our survey short and simple, there’s a lot we couldn’t ask about. If you’re interested in this topic, here are some questions you might consider:

- The role of negotiating non-salary benefits, like time off or flexibility.

- More granular differences among women of different races, non-binary, and transgender candidates.

- The influence of being required to state your desired salary when applying for the job.

- Differences among different industries and geographic areas

- A good dataset to look at for salary data (though not negotiation), is the Ask a Manager Salary Survey. Be sure to Take the survey yourself first.

Thanks to my teammates, Cassie Schmitt and Han Song, and to the people who took or promoted our survey!