And outsmart those who try to mislead you!

Recently I shared a series of posts on LinkedIn about staying honest when presenting data. Here’s a slightly deeper dive into what I shared and learned from the comments of fellow readers.

Be clear what you’re comparing to

“Senior Citizens in Atlanta are more likely to have poor access to transit.”

It’s common to hear this type of comparison made to support a claim, but it’s misleading because on its own it doesn’t tell us enough information. You could interpret this in one of several distinct ways:

- Seniors in Atlanta are more likely than seniors in other cities to have poor access to transit.

- Seniors in Atlanta are more likely than people of other age groups to have poor access to transit.

- Seniors in Atlanta are more likely to have poor rather than good access to transit.

These statements all mean somewhat different things and without more information, we can’t be sure what the speaker meant. Clarification will help reduce any misunderstandings. By the way, at least the first statement is true, according to a Transportation for America report documenting a growing problem of people aging in place in communities that lack good transit access.

Normalize Your Data with Caution

When you report data, you often need to normalize it: report it as a rate per capita, for example. But what you normalize it by is an important decision that can lead to very different outcomes.

In the post comments, a Bay Area acquaintance and I discussed how you should normalize the number of visitors to Golden Gate Park in San Francisco. It’s more difficult than it sounds, because normalizing by the number of residents ignores tourists who visit there, and anyway, which neighborhoods do you include in your population count?

I suggested that it depends on the context. In some cases, you don’t need to normalize – it’s not inaccurate to just say that Golden Gate Park has 12.4 million visitors per year. How you should normalize depends on what comparisons you are trying to draw. If you want to compare the popularity of Golden Gate Park to a park in a Bay Area suburb that fewer people have the chance to visit, it would be reasonable to normalize based on some combination of city residents and annual visitors to the city. If you want to compare it to a smaller park in San Francisco, you might want to normalize based on park acreage since the other park simply cannot hold as many people and does not touch as many neighborhoods.

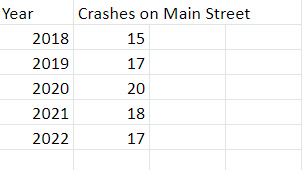

Watch the Y-Axis

There are few easier ways to lie with data than by truncating the y-axis on a graph. Consider the following:

The graphs look very different, but the underlying data is the same. Someone who wanted to suggest that trail usage was growing very fast might opt for the first one, but that would be misleading. The bottom graph, though less exciting, is a more honest way to represent what’s going on. When in doubt, think about if the trend were reversed and usage went down: Would you be so keen to zoom in on the differences then?

This is up for some debate. Seth Long makes a compelling argument that whether you truncate depends on if the difference you’re representing is significant in your particular context. This may be true for certain audiences, but most readers will not read carefully enough to understand that nuance, even if they are very educated and warned about y-axis truncation in advance, so I still think that truncations should be very limited.

Give Context to Trends

The last tip refers to the way we report data that changes over time. When you are reporting a trend, be clear about the timeline you are referring to and don’t selectively report just the time period that makes you look good.

If bus on-time performance has been been on the decline for 10 months but it’s still higher than it was at this time last year, you should give that full context and not merely say that it’s up. Or if last month finally saw a drop in bike thefts after a year of climbing, be clear that the reversal is recent. An easy way to spot a red flag with this type of data is when a politician at election time reports favorable numbers from the last three months and not their full term.

This report from the New York Times has great visualizations and shows how this technique is often manipulated to support partisan politics.

Wrapping it Up

What else do you find misleading when looking at data? Have you caught yourself lying with charts by accident? I’d love to hear your stories and other common pitfalls you think we should watch out for.